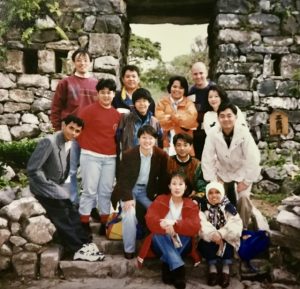

Asia Pacific Youth Forum (Okinawa, 1995)

“Keep learning, do good things, and do not harm other people,” said the old man to Nuon So Thero when he was a six-year-old boy struggling to stay alive in the horrors of the homicidal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia.

“Keep learning, do good things, and do not harm other people,” said the old man to Nuon So Thero when he was a six-year-old boy struggling to stay alive in the horrors of the homicidal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia.

Today Thero is an entrepreneur in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. He and his wife have a set of teenage twins who will soon be attending college. He runs his own businesses and holds leadership positions in several business and professional associations. He also oversees an orphanage that his mother started in a refugee camp at the Cambodian-Thai border.

Nuon So Thero (in blue suit, fourth from the right) colleagues at the Ministry of Information in May 2024.

However, Thero and so many of his generation do not take peace in the war-torn country of their youth or their personal success and happiness for granted. Millions of lives were lost and traumatized by the Khmer Rouge, a radical Communist movement that ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. A country that is blessed with fertile soil and people proud of their cultural heritage and historical place in Southeast Asia became known as the “Killing Fields.” The brutal and maniacal regime was determined to create a new order. No one was spared. Families were torn apart. Political opponents, teachers, writers, masters and practitioners of traditional arts, shopkeepers, farmers, and even children were summarily killed for the slightest offenses and perceived transgressions. An estimated 1.5 to 2 million Cambodians disappeared or died from starvation and extrajudicial killings by the time the bloody nightmare was over.

Thero, just six years old, was separated from this mother and sister (his father and a younger brother had already perished in the violence and chaos) and sent to a forced labor camp. Families were broken up, properties were seized or destroyed. Adults and children alike were herded to work daily and barely given enough to eat. There was no education or health care. Surviving another day was all one could do. He and his little friends shared their meager meals and any extra food they found by foraging. They tried to keep each other in good spirit but fear overcame them when time for sleep comes. Children in the camp woke up each morning to discover their friends, their bed mates, dead. Malnutrition, disease and stress were brutal on these little ones, but their young minds could not fathom what was taking their lives.

One morning Thero woke up to find four of his friends lifeless next to him. He was the only survivor in his little band of five. As was the routine, the limped little bodies were piled on carts and hauled away like dirty rags and buried nameless in a pit. Not long after that day, for reasons he could not fathom, the camp director decided time’s up for Thero. His little hands were tied to his back and taken into the forest. Just as he thought it was the end for him as he felt a knife’s blade on his neck, the man who took him to the forest cut him loose and set him free. For days this little six-year-old boy was in the forest on his own, eating anything he could find to stay alive. Then he saw a small village in the distance and an old man sitting all alone outside his wood-built hut. Out of desperation, Thero approached the old man thinking if only to ask for a last meal and drink before he is captured, killed or left to die on his own. The old man, who happened to be a village elder living alone, gave him food, shelter and protection. As the resistance forces with help from the Vietnamese army began to push the Khmer Rouge back, the old man sent Thero off to find his family and reminded the young boy to “keep learning, do good things, and do not harm other people.”

Good fortune was on his side again it seems. Even in the chaos of millions of displaced Cambodians fleeing from the Khmer Rouge, Thero soon reunited with his mother and sister. Fierce battles and skirmishes were everywhere as the Khmer Rouge forces retreated to the west of the country. Every step along the way, their determination, the kindness of strangers, and a bit of luck kept them out of harm’s way. It took three months on foot to reach Phnom Penh. Peace will not truly be established for several more years. By 1982 his family fled to refugee camps in the Cambodian-Thai border, hoping to find resettlement in a new land. This became home for their home for the next decade until they returned to Phnom Penh to start new lives. And it was here, at 11 years old, that Thero took his first step into a classroom. Though it was a delayed start to education, he has never stopped learning.

Thero stressed his participation in the Asia Pacific Youth Forum held in Okinawa, Japan, in 1995 critically exposed him to new ideas and energized him to make even greater effort to learn about the world beyond the boundaries of his job and his country. It was the first international trip for him as a young man in his mid-20s. It was the first time he flew in an airplane. It was the first time to hear so many voices from different parts of the world, personal backgrounds and professional fields. He was taken aback by some new things (raw fish in Japanese cuisine) while new ideas in participant presentations and hearty exchanges inside and outside formal sessions opened his mind and left a lasting impression on the importance of lifelong learning and using facts and sound arguments to discuss and debate rather than violence to settle difference. Education, facts, quality information and sound analysis…and hope, he came to see, are essential to peace in society. This has been his guiding philosophy in building a new life and in his leadership roles in business and charity work.

Thero stressed his participation in the Asia Pacific Youth Forum held in Okinawa, Japan, in 1995 critically exposed him to new ideas and energized him to make even greater effort to learn about the world beyond the boundaries of his job and his country. It was the first international trip for him as a young man in his mid-20s. It was the first time he flew in an airplane. It was the first time to hear so many voices from different parts of the world, personal backgrounds and professional fields. He was taken aback by some new things (raw fish in Japanese cuisine) while new ideas in participant presentations and hearty exchanges inside and outside formal sessions opened his mind and left a lasting impression on the importance of lifelong learning and using facts and sound arguments to discuss and debate rather than violence to settle difference. Education, facts, quality information and sound analysis…and hope, he came to see, are essential to peace in society. This has been his guiding philosophy in building a new life and in his leadership roles in business and charity work.

Nuon So Thero (in grey suit jacket, front left) at Asia Pacific Youth Forum in Okinawa in 1995.

His survival while so many around him died and good fortune to reunite with his family continue to motivate him to work to build peace and a new future in his country. His first jobs were with two non-profit organizations—American Assistance for Cambodia and Japan Relief to Cambodia (later renamed World Assistance for Cambodia)—that worked to build schools across Cambodia. About ten years ago, he left these organizations to begin a new career as an entrepreneur. By then some 550 schools, including 100 in former Khmer Rouge strongholds, have been constructed, staffed and equipped with Internet-connected computers to teach new generations of Cambodian children. He has also assumed leadership of the Future Light Organization (FLO), the orphanage started by his mother in the refugee camp that was his early childhood home. FLO takes in orphans and street children and offers them education, food and shelter, giving them a sense of safety and security when they need it most. Graduates of these institutions, Thero proudly says, are living meaningful lives and contributing to society as worker, parents, leaders and citizens. (His mother, Nuon Phaly, was awarded in 1998 the Magsaysay Award—Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel peace prize—for her work helping children at FLO and beyond.

Today most children in Cambodia fortunately do not live in violence, hunger or displacement. The generations that grew up in the last three decades, Thero says, know only of a largely peaceful and rapidly developing Cambodia. With smart phones in their hands and connections to the Internet, they are in a hurry to move forward for themselves and to see change in society. Education, he hopes, will give young people the tools to decipher what is honest and reliable information and to use it wisely. For someone who had lived through so much darkness in his early years, his firm beliefs in hope and peace continue to carry him forward and they are his aspirations for his countrymen and all societies.