This event now concluded. Report available here.

- Date: Wednesday, May 21, 2014, 7:00 pm

- Venue: Iwasaki Koyata Memorial Hall, International House of Japan

- Performance and Lecture:

Hans Tutschku (composer, US-Japan Creative Artists Program Fellow) - Language: English and Japanese (with consecutive interpretation)

- Program:

Issho ni 8-channel electroacoustic composition (2014, world premiere)

agitated slowness 8-channel electroacoustic composition (2010) - Co-sponsored by the Japan-US Friendship Commission (JUSFC)

- Supported by the Japanese Society for Sonic Arts, Japanese Society of Electronic Music, and Department of Intermedia Art, Tokyo University of the Arts

- Admission: Free (reservations required)

“I believe that stimulating curiosity is one of the most important aspects of education, human interaction, and art.”

“I believe that stimulating curiosity is one of the most important aspects of education, human interaction, and art.”

This lecture concert will present recent works, including a world premiere by the composer Hans Tutschku. He will introduce some of his artistic concepts and working methods that join sounds and artifacts from different continents into utopian, ritualistic performances.

Tutschku, originally from Germany, has lived for long durations in Holland, France, and the United States. He has traveled to more than 40 countries, always in search of typical sounds and musical encounters. He is known for his groundbreaking work in contemporary electroacoustic music. Tutschku also investigates the integration of technology in many other art forms and media, experimenting with oil painting, photography, theater, choreography, pottery, and video art. This experimentation has become an important source of inspiration for his music. His upbringing in communist East Germany was characterized by intense artistic collaborations and a constant yearning for the ability to express his ideas freely. The intensity of Tutschku’s works has not faded since the political change in 1989.

Tutschku’s Website www.tutschku.com/

Report

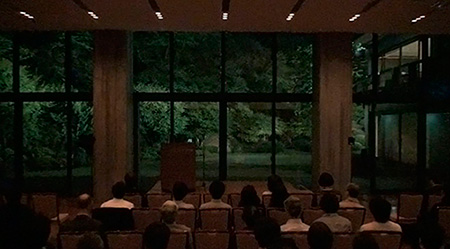

The electroacoustic musical compositions by Hans Tutschku differ from ordinary works in that they are not performed by musicians reading a score. They often consist of prerecorded sounds that are electronically reworked and “played” as complete works of music. Indeed, there were no musicians on stage at the IHJ Artists’ Forum in May 2014; instead, eight speakers, directed at the wall, surrounded the audience. As Tutschku began operating a terminal, all corners of the Iwasaki Koyata Memorial Hall were filled with sound—echoing off the walls—that was far more dynamic than anticipated.

Born in communist East Germany, Tutschku experienced the fall of the Berlin Wall while still a young man. Growing up behind a “seemingly impenetrable wall,” Tutschku noted, “stirred my interests for the world beyond the permitted perimeter.” As an adult he studied music in England, France, and the Netherlands, and has also continued to travel and live in many different countries. In each country he visited, he has directed his attention to the sounds of daily life and musical expressions unique to each locality and has utilized them in his compositions, giving special prominence to people’s voices. The pieces are created by mixing the sounds and voices recorded in various countries with musical phrases composed by Tutschku and performed with fellow musicians.

In the lecture, he gave a detailed illustration of the creative process by using the first work performed, titled Issho ni (Together), as an example. There is one segment of the piece that mixes a Bulgarian voice with a Scottish shepherd song. Instead of simply laying the two voices on top of one another, Tutschku adjusted the pitch slightly—being careful to maintain the dignity of the original—to achieve greater harmony. He played the unedited, original recordings as well to clearly illustrate, even to the untrained ear, how harmony can be amplified through this reworking process.

The technique creates an entrancing world of sound in which various ethnic groups sing in harmony with one another—probably impossible in real life. Issho ni literally brings together in one piece musical traditions that are separated by vast distances, sound environments that are inaccessible unless one actually travels there, and both the most sacred and commonplace of sounds and musical expressions. Even the sounds of countries in the midst of conflict embrace one another in innocent and peaceful harmony. Issho ni weaves together the expressions of countless cultures to create a utopia of sound that is so warmly human that it is hard to imagine it was generated electroacoustically. Originally produced as an installation, Issho ni was adapted as a concert piece, and its performance at the IHJ forum was the world premiere.

The second piece performed was created in a similar manner but on a higher level of abstraction. Originally produced for 24 speakers, it featured the same swelling musical development and ritual dynamism of Issho ni, and it would no doubt have been all the more awe-inspiring had there been three times the number of speakers. The seats in the hall were lined to face the window looking out on the I-House garden, so the audience was treated to scenes of trees swaying in the wind and the flight of birds and insects, as they listened to the performance. Sometimes, the music so exquisitely matched the movements in the garden that one wanted to believe that they were more than mere coincidences. Electroacoustic music has been described as “cinema for the ears,” and it could only have been held in the beautiful, garden-side setting of the Iwasaki Koyata Memorial Hall.