This event now concluded. Report available here.

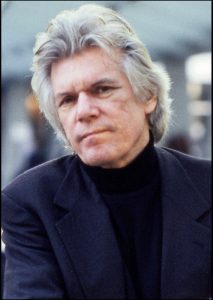

- Lecturer: Robert Whiting (Journalist)

- Date: Wednesday, June 20, 2018, 7:00-8:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm)

- Venue: Lecture Hall, International House of Japan

- Language: English (without Japanese interpretation)

- Admission: 1,000 yen (students: 500 yen, IHJ members: free)

- Seating: 100 (reservations required)

Since its introduction to Japan in the early Meiji Era, the grand old game of baseball has been the connective tissue that has bound the United States and Japan together for nearly a century and a half. This lecture will let us see the two countries’ relations through the prism of baseball.

First came to Japan in 1962 and has lived in Japan for nearly 40 years. After graduating from Sophia University with a degree in Japanese politics, he worked for Britannica Japan. His first book, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat (Dodd Mead, 1977), was chosen by TIME Magazine as the best sports book of the year. Mr. Whiting is the author of several highly acclaimed books on contemporary Japan, including You Gotta Have Wa (MacMillan, 1989; Vintage, 2009); Tokyo Underworld (Pantheon, 1999; Vintage, 2000), which describes organized crime in Japan and examines the corrupt side of the Japan-US relationship; and The Samurai Way of Baseball (Warner Books, 2005), which describes the impact of the outfielder Ichiro of the Seattle Mariners and other Japanese stars on U.S. baseball.

First came to Japan in 1962 and has lived in Japan for nearly 40 years. After graduating from Sophia University with a degree in Japanese politics, he worked for Britannica Japan. His first book, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat (Dodd Mead, 1977), was chosen by TIME Magazine as the best sports book of the year. Mr. Whiting is the author of several highly acclaimed books on contemporary Japan, including You Gotta Have Wa (MacMillan, 1989; Vintage, 2009); Tokyo Underworld (Pantheon, 1999; Vintage, 2000), which describes organized crime in Japan and examines the corrupt side of the Japan-US relationship; and The Samurai Way of Baseball (Warner Books, 2005), which describes the impact of the outfielder Ichiro of the Seattle Mariners and other Japanese stars on U.S. baseball.

Report

Baseball was introduced to Japan from the United States in 1872—a full decade before judo became a modern martial art and competitive sport. Yakyu, as baseball is called in Japan, subsequently evolved into a national pastime with its own distinctive style of play, game strategies, and coaching methods. At the I-House Lecture on June 20, journalist Robert Whiting traced the history of the sport as played in Japan and the United States and explored the role it has played in deepening the two countries’ relationship.

Baseball was introduced to Japan from the United States in 1872—a full decade before judo became a modern martial art and competitive sport. Yakyu, as baseball is called in Japan, subsequently evolved into a national pastime with its own distinctive style of play, game strategies, and coaching methods. At the I-House Lecture on June 20, journalist Robert Whiting traced the history of the sport as played in Japan and the United States and explored the role it has played in deepening the two countries’ relationship.

“Itching” to Play

Baseball was brought to Japan by Horace Wilson, a professor of English at the First Higher School (Ichiko; then the Tokyo Kaisei Gakko). Most of the students to whom he taught the game were sons of samurai, and the style of play was imbued with bushido ethics. Aoi Jutsuo, the team captain, for example, is said to have practiced his swing a thousand times a night. “Ichiko’s baseball was a test of manhood and fighting spirit,” Whiting noted. “It was forbidden to say ‘Ouch!’ in baseball practice because it was considered a sign of weakness. If someone’s nose was smashed by a batted ball and it really hurt, it was okay to say, ‘It itches.’”

The bushido code can still be seen today, Whiting says, in attitudes toward preseason training. “In America, spring training camp is short and easygoing. Players spend a lot of time on the golf course or at the swimming pool with their families. In Japan, spring training is long and intense, featuring marathon runs and exhausting drills.” The emphasis in the United States is on individual initiative, he continued, while the Japanese game is focused on “group harmony, or wa, and in making the great effort.” He went on to cite many differences in the two countries’ baseball culture, such as the frequency and content of meetings and game strategy.

Bridging the Pacific

Despite the differences in play, baseball has helped to bring the two countries closer together. “A 1934 tour by Babe Ruth and a team of Major League all-stars was a huge success and helped temporarily ease mounting war tensions,” Whiting said. “In 1949, a visit by the minor league San Francisco Seals proved a big hit and created an enormous store of good will,” leading to regular visits by Major League teams in subsequent years.

Star pitcher Nomo Hideo was a pioneer who charted a path for other Japanese players to achieve success in the Major Leagues. “Nomo’s popularity in America,” Whiting added “also helped ease bad feelings between the US and Japan over trade” and contributed to improving the trans-Pacific relationship.

Learning from Each Other

A steady stream of Japanese players have since moved to the Majors. “Perhaps the most famous was Ichiro Suzuki. He joined the Seattle Mariners in 2001 and won the MVP leading the team to a record 116 wins.” Two years later, he broke a single season batting record for hits that had stood for over 80 years. Other standouts include Matsui Hideki, who was selected in 2003 as one of the “25 Most Lovable People on the Planet” by People magazine, and “two-way” star Otani Shohei, who was named Rookie of the Year in 2018. These players, Whiting said, have improved the image of the Japanese, who were once seen in America as a faceless people obsessed with exporting cars and consumer electronics.

The resulting stronger interest in Major League baseball has led to greater openness in Japan toward American values and culture, not just in sports but in other areas of society as well. “Staples of Western-style individualism, such as headhunting, job hopping, and litigation—all taboo in the pre-Nomo era—became an accepted part of the culture,” Whiting said. Baseball, he concluded, “has taught us there is always something that we can still learn from each other.”