This event now concluded. Report available here.

- Lecturer: Katsura Sunshine (Rakugo storyteller)

- Date: Wednesday, June 28, 2017, 7:00-8:30 pm

- Venue: Iwasaki Koyata Memorial Hall, International House of Japan

- Language: English (without Japanese interpretation)

- Admission: 1,000 yen (500 yen for students; Free for IHJ members and guests staying at I-House on June 27 or 28)

Please note the downward adjustment of the admission price for this program series since April 2017. - Seating: 200 (reservations required)

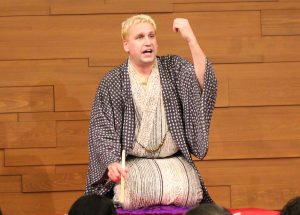

Katsura Sunshine

|

He came to Japan in 1999 to pursue studies in noh and kabuki theater. In September 2008, Sunshine was accepted as an apprentice to the great rakugo storytelling Master, Katsura Bunshi VI (then named Katsura Sanshi), and subsequently received the name Katsura Sunshine. In the rakugo tradition, he received both his master’s last name and part of the first (his master, Sanshi combined the first part of his name, “San,” meaning “Three,” with the Japanese word for “Shine,” and gave it the Japanese pronunciation of the English word “Sunshine”).Sunshine made his professional debut in Singapore the following year, and completed his three-year rakugo apprenticeship in November 2012. Sunshine is the first ever Western rakugo storyteller in the history of the “Kamigata” rakugo tradition, based in Osaka, and only the second ever in the history of Japan.

Sunshine has performed in Singapore, the United States and Canada, London, Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Oxford, Paris, Sydney, Adelaide, Canberra, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, Thailand, Ghana, Senegal, Gabon, and South Africa, as well as throughout Japan. He currently divides his time between London and Tokyo.

He has been appointed Cultural Ambassador for the Canadian Chamber of Commerce in Japan, and Friendship Ambassador for Japan and the Republic of Slovenia. He is also Artist in Residence at The Forge Venue in Camden, London. Katsura Sunshine website

Report

Katsura Sunshine, Japan’s first professional English rakugo performer in the postwar era, provides amusing insight into the charms of rakugo and his experiences on English rakugo tours abroad.

Figuring out how to render classical rakugo in English

Every time he takes the stage, Sunshine starts with a standard spiel in Japanese, introducing himself by explaining his name—the kanji for ‘katsura,’ ‘three,’ and ‘shine,’ making “Katsura Sunshine”—and explaining that he’s a genuine rakugo performer, the 15th apprentice of Katsura Bunshi, despite not exactly looking the traditional part. He then closes with a standard “domo,” an all-purpose Japanese term that proves tough to translate into English. Over the years, Sunshine has created English versions of countless classical rakugo pieces and given performances across the globe. He prefaces each one with an introduction of all things rakugo, including phrasing and gestures, to give his audiences a funny, informative initiation into one of Japan’s most distinctive cultural assets.

The first time Sunshine tried to translate classical rakugo into English, he ran into a mountain of challenges. Some of the thorniest difficulties had to do with the things that escape direct translation, the elements that don’t have one-to-one equivalents: natively Japanese puns and wordplay, for example, and outdated turns of phrase. For non-natives, rakugo teems with features that can be indecipherable. Even Sunshine, a nine-year veteran of the professional rakugo scene, has to grapple with some phrases numerous times before he can make sense of them.

How are you supposed to translate “Oyabun, katajikenai!”

Take the expression “Oyabun, katajikenai,” for example. The phrase is rife with complex emotions: respect and gratitude toward the speaker’s oyabun (boss), first of all, with a twinge of self-deprecation running through the wording. The phrase ends up going flat in English, though, losing the nuance of the original. A simple “Thank you, chief” doesn’t have the right connotations to it.

Whenever he sets to explaining the language of his medium, Sunshine makes a point of translating uniquely Japanese phrases into English word for word. The renderings—almost always a bit strained—help him highlight the inherent differences between the two languages and paint the underlying Japanese cultural contexts in a funnier, more entertaining light. “Dozo, yoroshiku onegai itashimasu,” a ubiquitous expression in everyday Japanese, is couched in layers and layers of honorifics. That makes for an ornately stilted verbiage in direct translation, something along the lines of “I thank you for your kindness in advance”—and the almost gratuitous etiquette of the rendering reveals the inherently polite overtones of the Japanese language. During his performances for foreign audiences, these sorts of examples help Sunshine spotlight the humility of Japanese culture in an intuitive way.

What makes rakugo so special?

Sunshine says that rakugo has a universal pull. Why do his performances overseas—which almost never stray from the original Japanese stories—make foreign audiences laugh? To Sunshine, it’s because of the fundamentally “human” narrative contexts underpinning all the jokes in a rakugo performance. From bickering spouses to straight-man/funny-man pairings and bungling burglars, rakugo stories are filled with characters and situations that you can find anywhere. You don’t need any prior knowledge of Japanese culture to get a kick out of the content. While its core comedic components have a universal reach, rakugo is also sprinkled with such a plethora of Japanese cultural ingredients that spectators can learn about Japan just by listening to a story. For Sunshine, that’s one of the things that make rakugo so compelling.

Entertainment that transcends time and language

The history of rakugo dates back around 400 years to the age of Edo, a time and place that couldn’t be more different from contemporary Tokyo society. Over that span, Japan’s language and culture have undergone massive transformations. Rakugo, however, has remained a solid constant—with masters tirelessly passing their skills on to apprentices, centuries and centuries of performers have won the hearts of the young and old alike. The locality of the art form, once specific to Japan, has also faded away ; from Tokyo to New York and Senegal, audiences are engaging with the stories in English, French, Japanese, and a host of other languages. It’s now a brand of worldwide entertainment, one that hasn’t fallen victim to the perils of age. “Rakugo stories never get into religion, politics, or race, and there’s never any swearing,” Sunshine explains, extolling some of the virtues that have made rakugo such a timeless comedic tradition. “If you’re looking for a simple, innocent art form that the whole family can enjoy together, rakugo is it.”